Type Rocket

Type Rocket 60 is an online Firework game for kids. It uses the Flash technology. Play this Letter game now or enjoy the many other related games we have at POG. There are many different types of model rockets and one of the first and simplest type of rocket that a student encounters is the bottle rocket. We have an entire section of the Beginner's Guide to Rockets, devoted to the science and math of bottle rockets.

The Multi-Barrel Rocket Launcher (MBRL) has 12 tubes arranged in three lines of four tubes each. All the tubes are parallel to each other and mounted co-axially on a cradle. Ammunition used with the MBRL is in the form of Rocket which consists of one piece. Warhead is attached with rocket motor. A fixed amount of propellant is contained in the rocket motor. The rocket is stabilized with a slow spin.

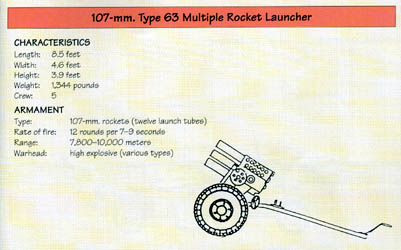

The Type 63 (12-round) MRS is mounted on a rubber-tire split pole type carriage, while the Type 63-I is a packed model for airborne and mountain units. The Type 85 is a single manportable tripod-mounted launcher tube for use by special forces units. The NORINCO Type 81 (12-round) is mounted on a 4X4 truck, with a enlarged cab to accommodate the crew of four and 12 reload rounds. The vehicle suspension is locked for firing, and the entire system can be dismounted from the vehicle and placed on a tow carriage. The launcher can be fired from the cab or from a remote position.

Several variants of North Korean design and manufacture are known to exist [which are evidently without a formal designation in the open literature], in addition to the basic configuration of 12 launch tubes in array of 3 rows of 4 tubes. Two other North Korean self-propelled versions exist: one with 18 tubes and one with 24 tubes. As with the Chinese variants, the North Korean 12-tube launcher can also be can be towed or mounted on a 4 leg stand, or mounted on any suitable wheeled or tracked vehicle.

The Type 63 HE-Fragmentation Spin-Stabilized Rocket is an electrically initiated, rocket incorporating a high-explosive fragmentation warhead. It is normally fired from a trailer- or truck-mounted multiple launcher, but may also be fired from single-tube launchers mounted on small boats. It is a barrage weapon used against personnel and material. Rockets of early manufacture are painted battleship gray or dark green; later rockets are olive drab. The bourrelets and nozzle plate are unpainted. Markings, stenciled in black and providing manufacturing data and nomenclature, may vary on individual rockets. Setscrews lock the adapter to the warhead and the adapter and nozzle plate to the rocket motor. The nozzle closure screws over the base of the nozzle plate. A hole in the center of the nozzle closure is crimped around an insulated stud in the center of the initiator assembly, thus waterproofing the base of the rocket motor. The initiator assembly electrical contact is exposed through the center of the insulated stud. The nozzles are canted to provide spin.

The Type 63-2 Rocket is an 18.8-kilogram (41.5-pound) rocket containing a main charge of TNT weighing 1.3 kilograms (2.9 pounds). The rocket is olive drab with black markings. The warhead is made of metal.

The 107mm spin stabilized incendiary rocket contains an unknown amount of White Phosphorous (WP). The rocket is painted olive drab with black markings. The warhead is made of metal.

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

Chemical propellants in common use deliver specific impulse values ranging from about 175 up to about 300 seconds. The most energetic chemical propellants are theoretically capable of specific impulses up to about 400 seconds.

High values of specific impulse are obtained from high exhaust-gas temperature, and from exhaust gas having very low (molecular) weight. To be efficient, therefore, a propellant should have a large heat of combustion to yield high temperatures, and should produce combustion products containing simple, light molecules embodying such elements as hydrogen (the lightest), carbon, oxygen, fluorine, and the lighter metals (aluminum, beryllium, lithium).

Another important factor is the density of a propellant. A given weight of dense propellant can be carried in a smaller, lighter tank than the same weight of a low-density propellant. Liquid hydrogen, for example, is energetic and its combustion gases are light. However, it is a very bulky substance, requiring large tanks. The dead weight of these tanks partly offsets the high specific impulse of the hydrogen propellant.

Other criteria must also be considered in choosing propellants. Some chemicals that yield excellent specific impulse create problems in engine operation. Some are not adequate as coolants for the hot thrust-chamber walls. Others exhibit peculiarities in combustion that render their use difficult or impossible. Some are unstable to varying degrees, and cannot be safely stored or handled. Such features inhibit their use for rocket propulsion.

Unfortunately, almost any propellant that gives good performance is apt to be a very active chemical; hence, most propellants are corrosive, flammable, or toxic, and are often all three. One of the most tractable liquid propellants is gasoline. But while it is comparatively simple to use, gasoline is, of course, highly flammable and must be handled with care. Many propellants are highly toxic, to a greater degree even than most war gases; some are so corrosive that only a few special substances can be used to contain them; some may burn spontaneously upon contact with air, or upon contacting any organic substance, or in certain cases upon contacting most common metals.

Also essential to the choice of a rocket propellant is its availability. In some cases, in order to obtain adequate amounts of a propellant, an entire new chemical plant must be built. And because some propellants are used in very large quantities, the availability of raw materials must be considered.

Two general types of solid propellants are in use. The first, the so called double-base propellant, consists of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine, plus additives in small quantity. There is no separate fuel and oxidizer. The molecules are unstable, and upon ignition break apart and rearrange themselves, liberating large quantities of heat. These propellants lend themselves well to smaller rocket motors. They are often processed and formed by extrusion methods, although casting has also been employed.

The other type of solid propellant is the composite. Here, separate fuel and oxidized chemicals are used, intimately mixed in the solid grain. The oxidizer is usually ammonium nitrate, potassium chlorate, or ammonium chlorate, and often comprises as much as four-fifths or more of the whole propellant mix. The fuels used are hydrocarbons, such as asphaltic-type compounds, or plastics. Because the oxidizer has no significant structural strength, the fuel must not only perform well but must also supply the necessary form and rigidity to the grain. Much of the research in solid propellants is devoted to improving the physical as well as the chemical properties of the fuel.

Ordinarily, in processing solid propellants the fuel and oxidizer components are separately prepared for mixing, the oxidizer being a powder and the fuel a fluid of varying consistency. They are then blended together under carefully controlled conditions and poured into the prepared rocket case as a viscous semisolid. They are then caused to set in curing chambers under controlled temperature and pressure.

Solid propellants offer the advantage of minimum maintenance and instant readiness. However, the more energetic solids may require carefully controlled storage conditions, and may offer handling problems in the very large sizes, since the rocket must always be carried about fully loaded. Protection from mechanical shocks or abrupt temperature changes that may crack the grain is essential.

Most liquid chemical rockets use two separate propellants: a fuel and an oxidizer. Typical fuels include kerosene, alcohol, hydrazine and its derivatives, and liquid hydrogen. Many others have been tested and used. Oxidizers include nitric acid, nitrogen tetroxide, liquid oxygen, and liquid fluorine. Some of the best oxidizers are liquified gases, such as oxygen and fluorine, which exist as liquids only at very low temperatures; this adds greatly to the difficulty of their use in rockets. Most fuels, with the exception of hydrogen, are liquids at ordinary temperatures.

Certain propellant combinations are hypergolic; that is, they ignite spontaneously upon contact of the fuel and oxidizer. Others require an igniter to start them burning, although they will continue to burn when injected into the flame of the combustion chamber.

In general, the liquid propellants in common use yield specific impulses superior to those of available solids. On the other hand, they require more complex engine systems to transfer the liquid propellants

87162 °-59-4

to the combustion chamber. A list showing solid- and liquid-propellant performance is given in table 1.

- Propellant combinations: Isp Range

- Low-energy monopropellants________________________ 160 to 190.

- Hydrazine

- Nitromethane_______________________________ 190 to 230

- Low-energy bipropellants___________________________ 200 to 230.

- Perchloryl fluoride-Available fuel

- Hydrazine-Acid

- Liquid oxygen-JP-4

- Liquid oxygen and fluorine-JP-4

- Fluorine-Hydrogen

- Potassium perchlorate:

- Thiokol or asphalt_____________________________ 170 to 210.

- Thiokol_____________________________________ 170 to 210.

- Polyester____________________________________ 170 to 210.

Rubber_____________________________________ 170 to 210.

Nitropolymer_________________________________ 210 to 250.

Liquid oxygen is the standard oxidizer used in the largest United States rocket engines. It is chemically stable and noncorrosive, but its extremely low temperature makes pumping, valving, and storage difficult. If placed in contact with organic materials, it may cause fire or an explosion.

Nitric acid and nitrogen tetroxide are common industrial chemicals. Although they are corrosive to some substances, materials are available which will safely contain these fluids. Nitrogen tetroxide, since it boils at fairly low temperatures, must be protected to some degree.

Liquid fluorine is a very low temperature substance, comparable with liquid oxygen, and is highly toxic and corrosive as well. Furthermore, its products of combustion are extremely corrosive and dangerous; hence, the use of fluorine raises problems in testing and operating rocket engines.

Most liquid fuels, with the exception of hydrogen, are closely alike in performance and handling. They are usually quite tractable substances. Hydrogen, however, exists as a liquid only at extremely low temperatures-lower even than liquid oxygen; hence, it is very difficult to handle and store. Also, if allowed to escape into the air, it can form a highly explosive mixture. It is a very bulky substance, about one-fourteenth as dense as water. Nonetheless, it offers the best performance of any of the liquid fuels.

Certain unstable, liquid chemicals which, under proper conditions, will decompose and release energy, have been tried as rocket propellants. Their performance, however, is inferior to that of bipropellants or modern solid propellants, and they are of most interest in rather specialized applications, like small control rockets. Outstanding examples of this type of propellant are hydrogen peroxide and ethylene oxide.1

The use of more than two chemicals as propellants in rockets has never received a great deal of attention, and is not considered advantageous at present. Occasionally a separate propellant is used to operate the gas generator which supplies the gas to drive the turbopumps of liquid rockets. In the V-2, for example, hydrogen peroxide was decomposed to supply the hot gas for the main turbopumps, although the main rocket propellants were alcohol and liquid oxygen.

If certain molecules are torn apart, they will give up large amounts of energy upon recombining. It has been proposed that such unstable fragments, called free radicals, be used as rocket propellants. The difficulty is, however, that these species tend to recombine as soon as they are formed; hence, a central problem in their use is development of a method of stabilization. Atomic hydrogen is the most promising of these substances. Use of atomic hydrogen might yield a specific impulse of about 1,200 to 1,400 seconds.2

Devices such as the nuclear rocket must use some chemical as a working fluid or propellant, although no energy is supplied to the rocket by any chemical reaction. All the heat comes from the reactor. Since the prime consideration is to minimize the molecular weight of the exhaust gas, liquid hydrogen is the best substance so far considered

1 North American Aviation, Inc., press release NL-45, October 15,1958.

2 Outer space Propulsion Using Nuclear Energy, hearings before subcommittees of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, Congress of the United States 85th Cong., 2d sess., January 22, 23, and February 6, 1958, Lt. Col. P. Atkinson, p. 145.

Type Rocket Game

, and it does not seem likely that any substance with superior performance can be found. The problems of handling liquid hydrogen are the same for the nuclear rocket as for the chemical rocket.

Type Rocket 60

Another substance mentioned for use as a propellant in the nuclear rocket is ammonia. While offering only about one-half the specific impulse of hydrogen for the same reactor temperature as a consequence of its greater molecular weight, it is a liquid at reasonable temperatures and is easily handled. Its density is also much greater than hydrogen, being about the same as that of gasoline.

Propellants that would be suitable for use in electric propulsion devices are the easily ionized metals. The one most generally considered is cesium; next best are rubidium, potassium, sodium, and lithium.

Some unconventional approaches in the propellant field include the following:

Type Rocket Jr

3 Encapsulated Liquid Fuel Study Initiated, Aviation Week, vol. 69, No. 19, November 10, 1958, p. 29.

Type Rocket Launch